Exotic Africa meets Ignorant Europe

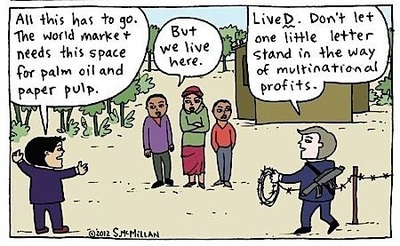

It is sad but true that honest help, respect and sustainability seemed to be foreign words in the ears of colonists, as well in terms of the development of publishing culture on the African continent. The work of colonists was thorough and imperialism affected more than just the economy and politics: it dominated the culture as well. But to what extent can we say that British colonial and postcolonial publishing was a significant vehicle of cultural imperialism?

Going back to the beginning we can see that

Going back to the beginning we can see that

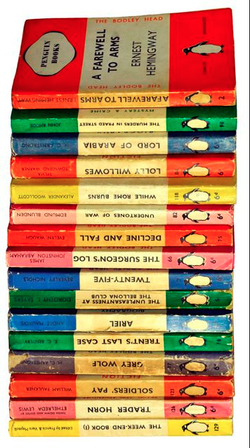

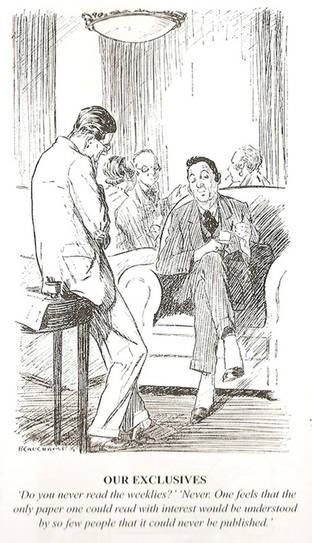

the big British publishers regarded West Africa only as a place where you sold books, not where you published them.

The idea that you could publish books by African authors, and especially by creative writers, had not yet occurred to these great houses, whose only concern was to make money out of the expanding school market. (Hill: 122)

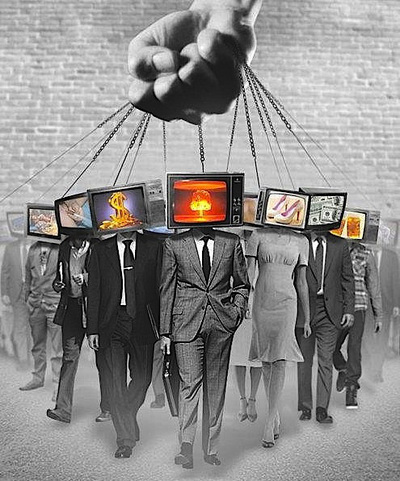

This idea of Africa as a lucrative market was supported by the missionary schools and the administrative/ governmental offices promoting British culture, literature, language, etc. among the African population. The money made in West Africa went back home to Europe with the publishers and the industry was still far from investing and encouraging in local publishing or authors. Culture was made in Europe and then sold in the rest of the empire. This odd behaviour explained Said as the "general European effort to rule distant lands and people. "(Said: xi) justified by the argument that "'they' were not like 'us', and for that reason deserved to be rule." (Said: xii)

But change was to come and the understanding of culture as source of identity led, finally, to a publishing of African literature and the search for African writers. But can we really talk of an understanding of African culture or was it just feeding the Western beliefs with exotic myths?

Huggan puts the main issue in a nutshell, asking

Huggan puts the main issue in a nutshell, asking

what is African literature? […] African literature from which region? […] African literature in which language? For African literature […] largely means literature in English, French and other European languages

(Huggan: 34)

| Is this cultural African identity? Not really. It seems to be the idea of the Western culture thinking that it understands the colony better than the colony itself. Ngugi wa Thiong'o goes one step further talking about controlled writing and publishing as a form of linguistic imperialism. This is still true for the situation today I guess, although I can just speculate. To be honest, I think that even though the situation might have developed positively, there are still many dark and mysterious pages in the history of colonial and postcolonial publishing. |

Ngugi Wa Thiong'o confirms these thoughts saying that: "Africa is dominated by a hand full of languages, and those from Africa have been completely marginalised. [...] European languages determine everything [...] they take the space of knowledge that used to be occupied by African languages. [...] European languages contain a wealth of material and there is no reason why this should not be available in African languages." (2008)

I think that these facts show very well that globalisation in Africa is still very dominated by European thinking and taste.

I think that these facts show very well that globalisation in Africa is still very dominated by European thinking and taste.

| | |

English is not an African language. (Ngugi Wa Thion'o)

Very interesting viewpoints of an African writer on this topic.

Very interesting viewpoints of an African writer on this topic.

| Biography Hill, Alan. In Pursuit of Publishing. London: Murray, 1988, pp. 120-124. Huggan, Graham. The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 34-57. Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage Books, 1998, pp. xi-xv. Ngugi wa Thiong'o. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literatures. Oxford: James Currey, EAEP, Heinemann, 1986, pp. 69-71. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed